RESEARCH CONTEXT

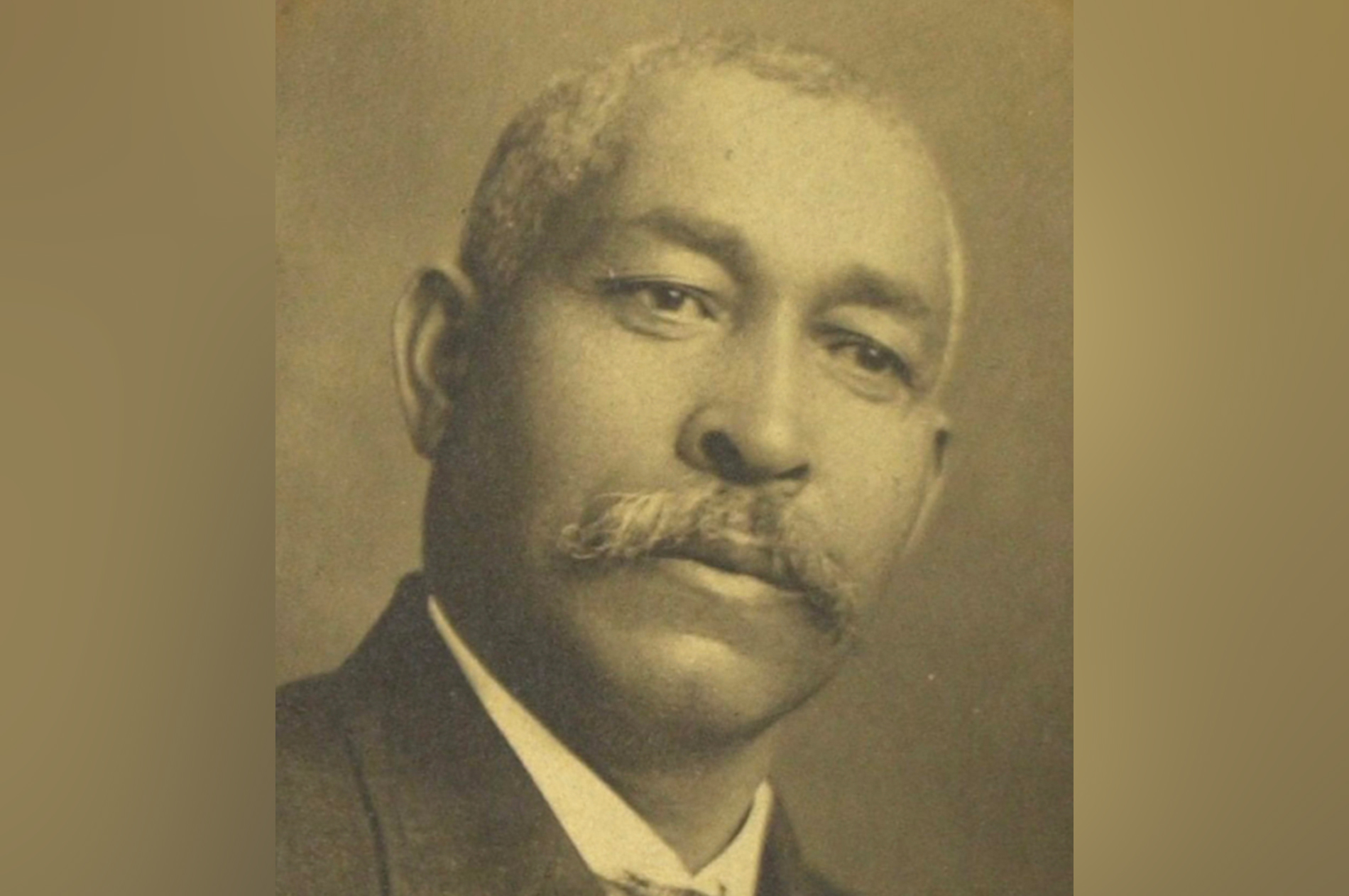

Fig. 1 - Dr. Manessa Pope |

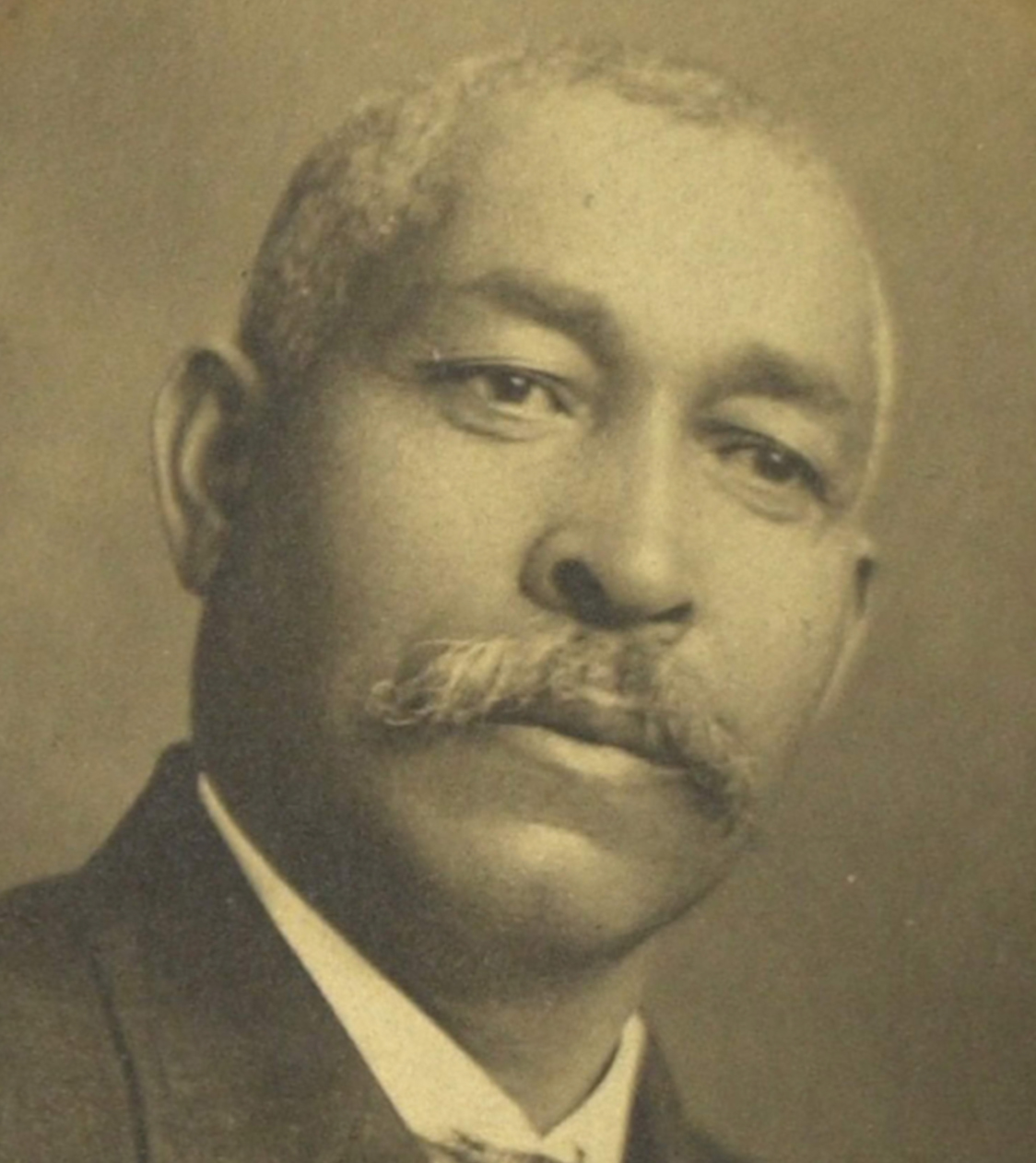

Fig. 2 - North Carlonia, USA |

What if we could travel back to the 20th century, the year is 1901. Dr. Manessa Thomas Pope (Fig. 1)  , one of Raleigh, North Carolina’s (Fig. 2)

, one of Raleigh, North Carolina’s (Fig. 2)  most prominent African American physician, serviceman, and politician is laying the foundation for his home (Fig. 3)

most prominent African American physician, serviceman, and politician is laying the foundation for his home (Fig. 3) that over a century later would remain standing in downtown Raleigh as a symbol of perseverance, community, and civic identity.

that over a century later would remain standing in downtown Raleigh as a symbol of perseverance, community, and civic identity.

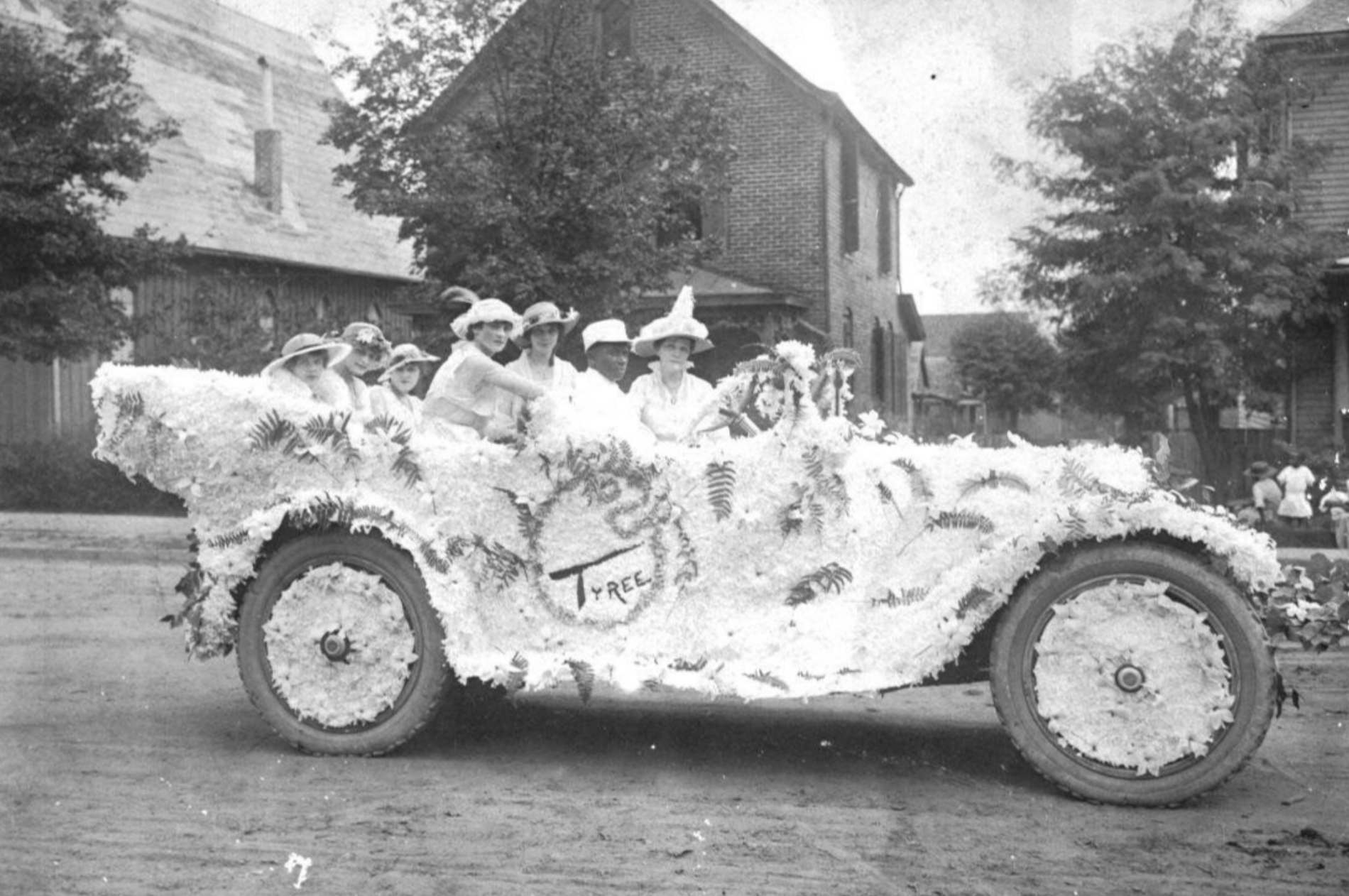

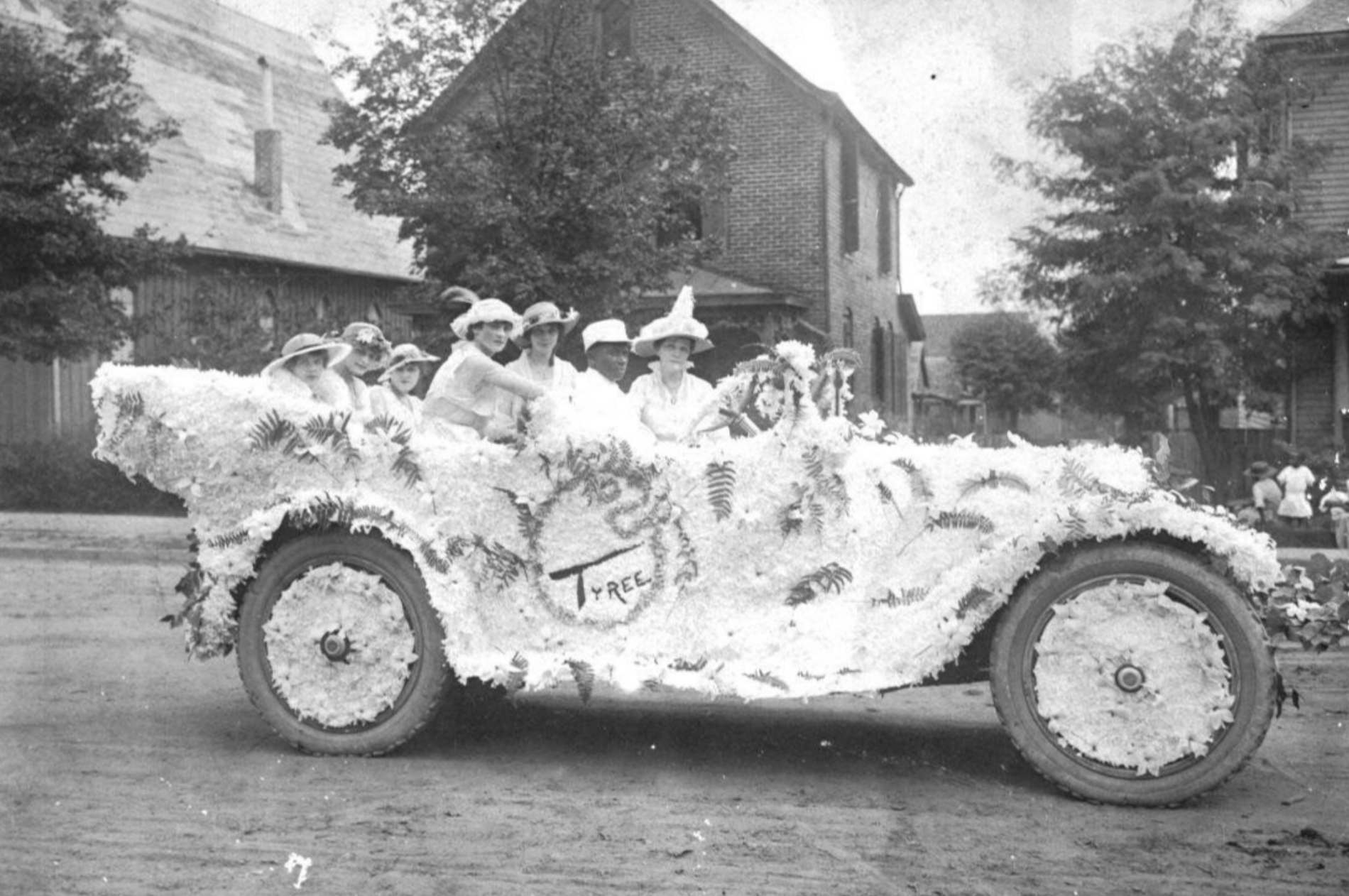

Fig. 3 - Historic exterior photo of the Pope House

Fig. 3 - Historic exterior photo of the Pope HouseWhile we don’t have the means to physically time travel, current advancements in immersive technology have given us a taste of what it feels like to step back in time to re-experience history. The I AM A MAN VR Experience (Fig. 4)  , the vMLK project (Fig. 5)

, the vMLK project (Fig. 5)  , and Ann Frank House (Fig. 6)

, and Ann Frank House (Fig. 6) , are among leading immersive experiences that takes us back in time to relive and re-experience historical events that teach us not only about those that came before us but also provide a space for us to reflect on our own lives and the future we are all working towards.

, are among leading immersive experiences that takes us back in time to relive and re-experience historical events that teach us not only about those that came before us but also provide a space for us to reflect on our own lives and the future we are all working towards.

Fig. 4 - I AM A MAN VR |

Fig. 5 - Virtual MLK VR |

Fig. 6 - Anne Frank House VR |

Fig. 7 - Virtual MLK VR Preview

Before the emergence of immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, House museums metaphorically represented a time machine through which we could step into a historic period and walk in the same spaces as those that once lived in the home.

"House museum produces knowledge grounded in the common experience of home, which contributes to collective identity and affirms national or local characteristics." Linda Young |

"House museum calls up feelings and memories in visitors more than does any other type of museum." Monica Risnicoff de Gorgas |

"[House] Museums are instruments of communication." Giovanni Pinna |

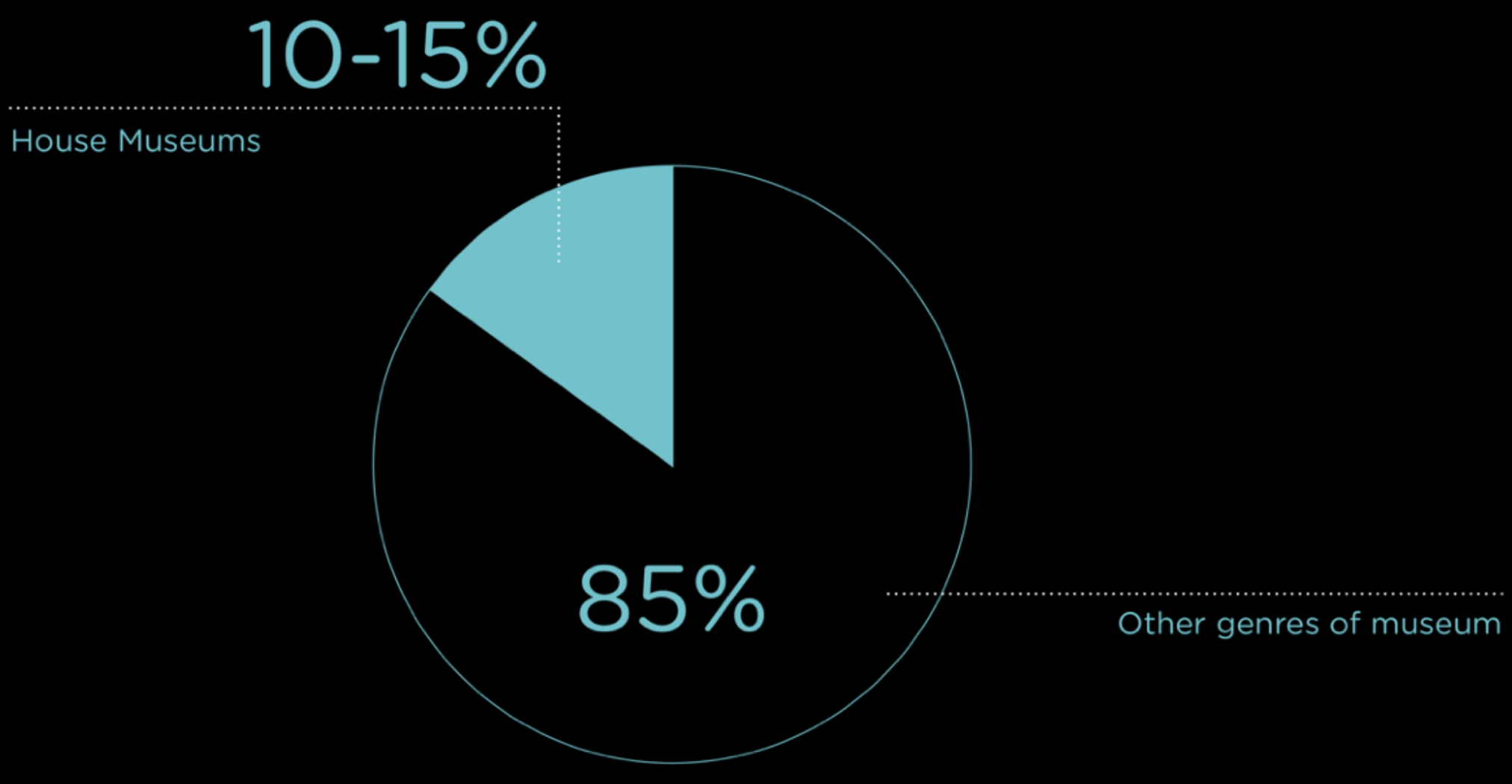

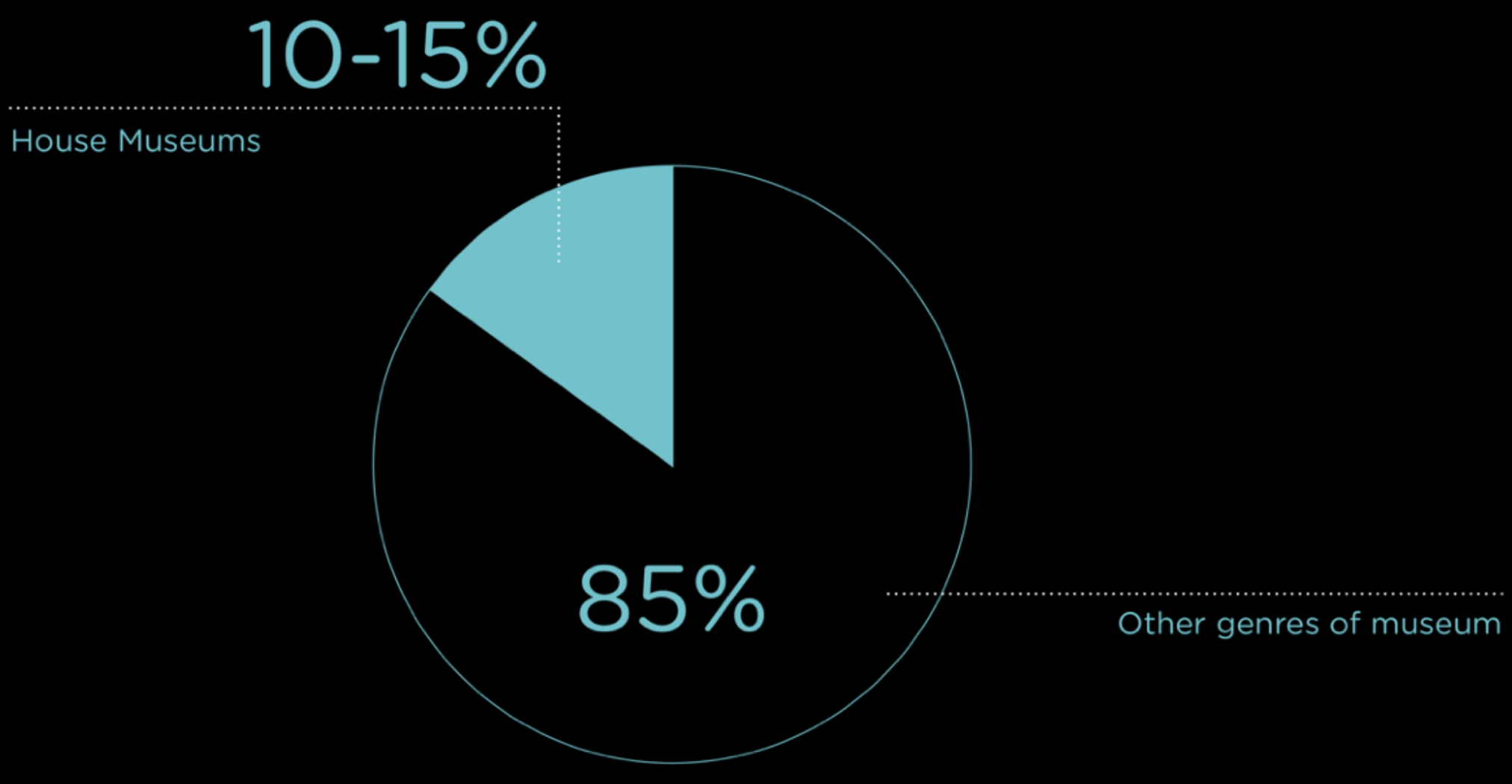

Approximately, 10-15 percent of all museums, (Fig. 8)  House Museums are invaluable cultural and social apparatuses that communicate not only the homeowners’ lived experiences but also embody national and local identity.

House Museums are invaluable cultural and social apparatuses that communicate not only the homeowners’ lived experiences but also embody national and local identity.

Fig. 8 - Percentage of House Museums

The Pope House Museum (Fig. 9)  located in downtown Raleigh, North Carolina is the only historic home built and occupied by an African American family in North Carolina. Unfortunately, the Pope House, like many house museums nationwide in the United States are facing difficulties enticing museum visitors and generating enough revenue to keep the doors open.

located in downtown Raleigh, North Carolina is the only historic home built and occupied by an African American family in North Carolina. Unfortunately, the Pope House, like many house museums nationwide in the United States are facing difficulties enticing museum visitors and generating enough revenue to keep the doors open.

Fig. 9 - Pope House Museum

Fig. 9 - Pope House Museum"House Museums are dying every day"

Ernest Dollar - Director, City of Raleigh Museum

In an interview with Ernest Dollar, director of the City of Raleigh Museum, he stated that house museums are dying every day. Factors contributing to the decline of House Museum are:

The lack of governmental support and visitors unwillingness to pay more for museum experiences. |

The immutable nature of historic homes and the impossibility of changing its meaning. |

House museums primary emphasis on educational activities |

The challenging task of implementing modern technology in historic homes. |

RESEARCH METHODS

After identifying these problems, I proposed the following research and subquestions question to guide my investigation:

How can the design of mixed reality systems be implemented in historic house museums to increase the experiential value of a visit?

Subquestions I explored are:

How might the system incorporate design elements to expound upon the possible narrative of material artifacts? |

How might the system bridge a connection between the history within the home to the broader historical narrative of the community within which the homeowner lived? |

How might the system adapt to the specific needs and interests of visitors and enable them to customize their visitation experience? |

I began my investigation with an observation study at the Pope House. The primary focus of the observational study was to understand how docents guide visitors during a tour at the Pope House Museum. A secondary focus of the study was to understand how visitors moved through the museum and interact with artifacts present in the home. Using a semi-structured observational approach, the researcher occasionally participated in the tour alongside visitors.

In semi-structured interview sessions, I spoke with Ernest Dollar, Director of the City of Raleigh Museum, and Edna Ballentine, a former caretaker of the Pope House, to understand their unique perspectives and involvement with the museum. I also spoke with visitors to understand their motivations for coming to the Pope House. The interview approach was semi-structured, allowing for flexibility in conversations with the interviewees.

To understand current and emerging uses of mixed reality systems, I reviewed extended reality (XR) experiences and the means through which curators and educators implemented them within and outside of the museum environment. I analyzed the means through which visitors and participants accessed and experienced each application. From the analysis, I drew key functionalities of the experiences most applicable to the implementation of mixed reality systems into house museums.

Based on the information gathered from the observational study at the Pope House Museum, I developed personas of visitors to situate design explorations and ground the investigation in a human-centered research approach. The journey map articulates how docents guide visitors during a visitation tour before the implementation of the mixed reality system. During the development of the prototype, I revised the journey map to express how the implementation of the mixed reality system would change the museum visitation experience. Persona’s I developed included, Henry a History teacher whose motivation for visiting the museum is to get a holistic understanding of the Pope family history. And Natalie, a graduate student at Shaw University who is interested in learning about the Pope family home life.

I developed a functional prototype of an AR mobile application for the Pope House Museum in Raleigh, NC. User testing the prototype was essential to understanding which elements of the AR mobile application were the most successful or challenging to implement based on various conditions within the museum.

CONCEPTUAL MATRIX

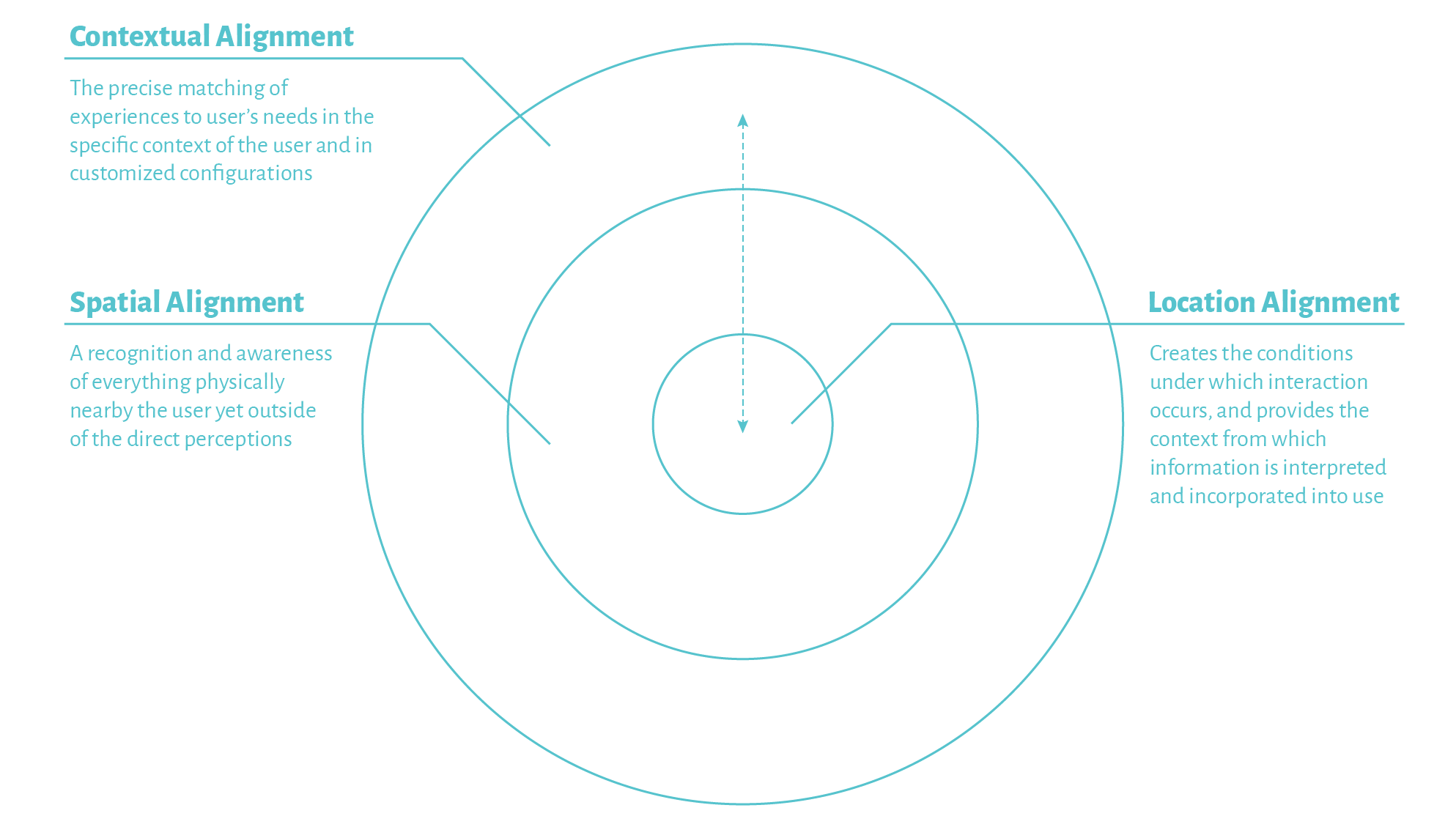

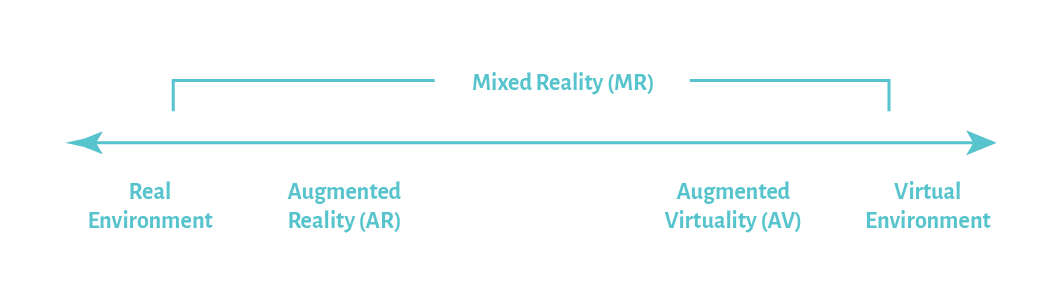

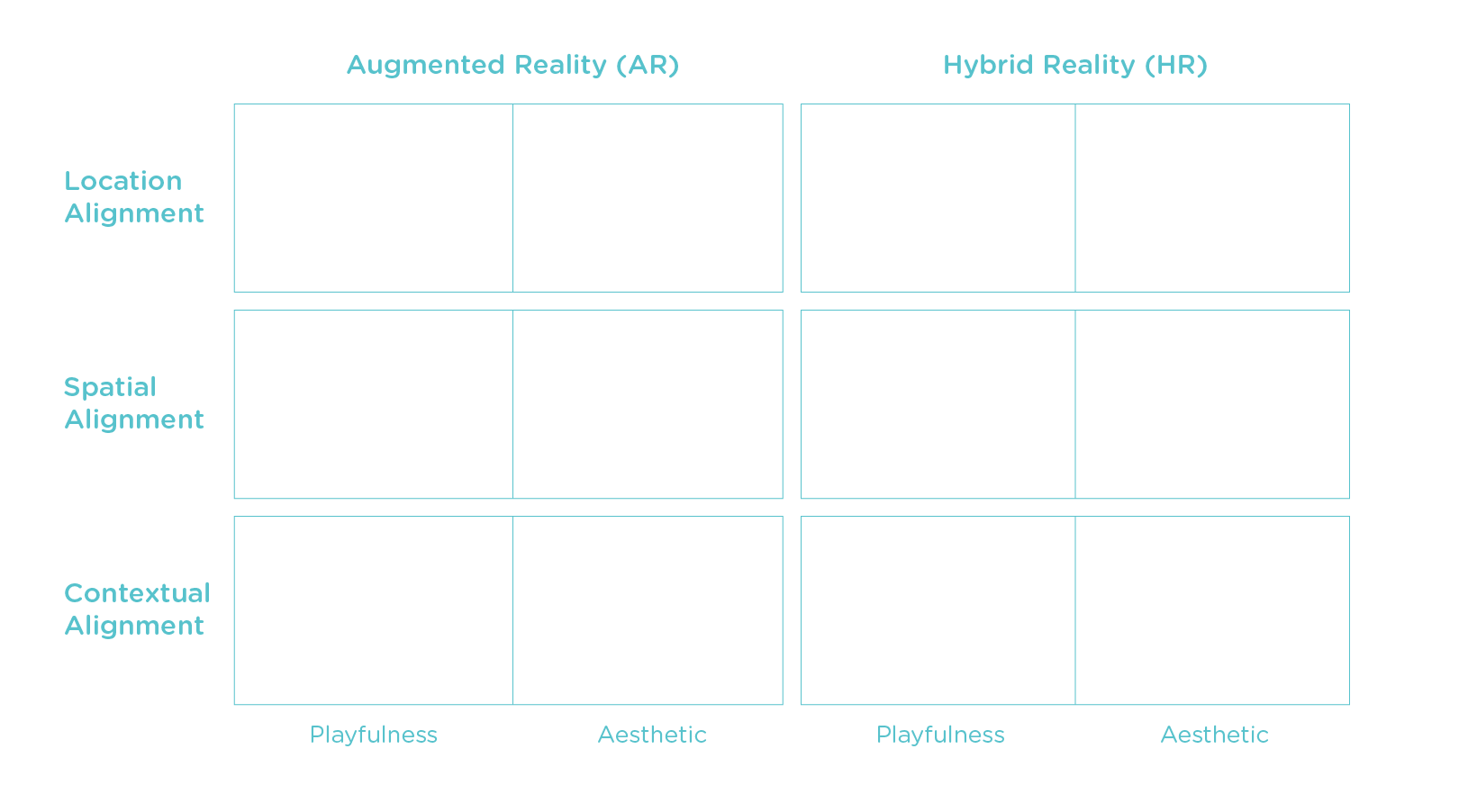

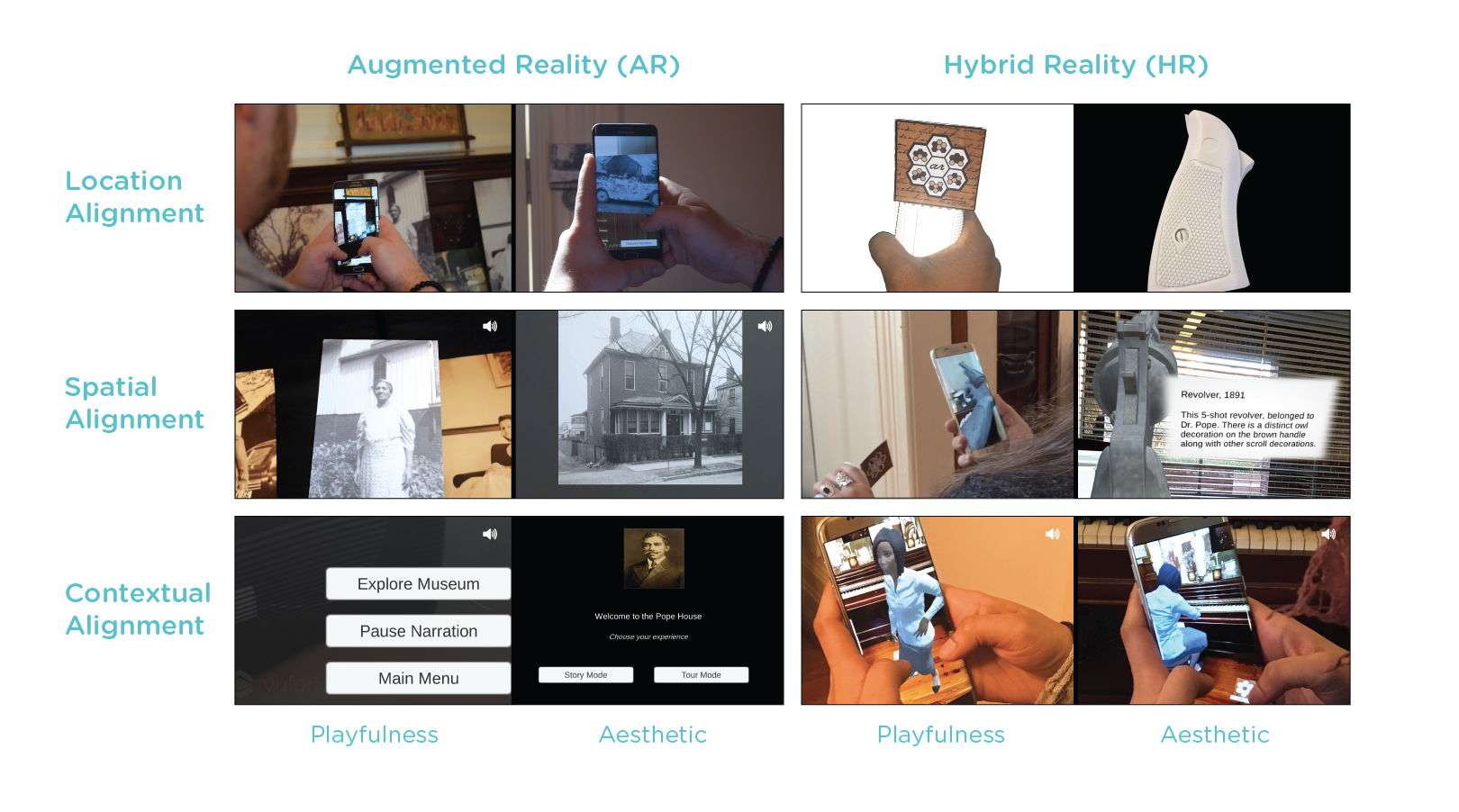

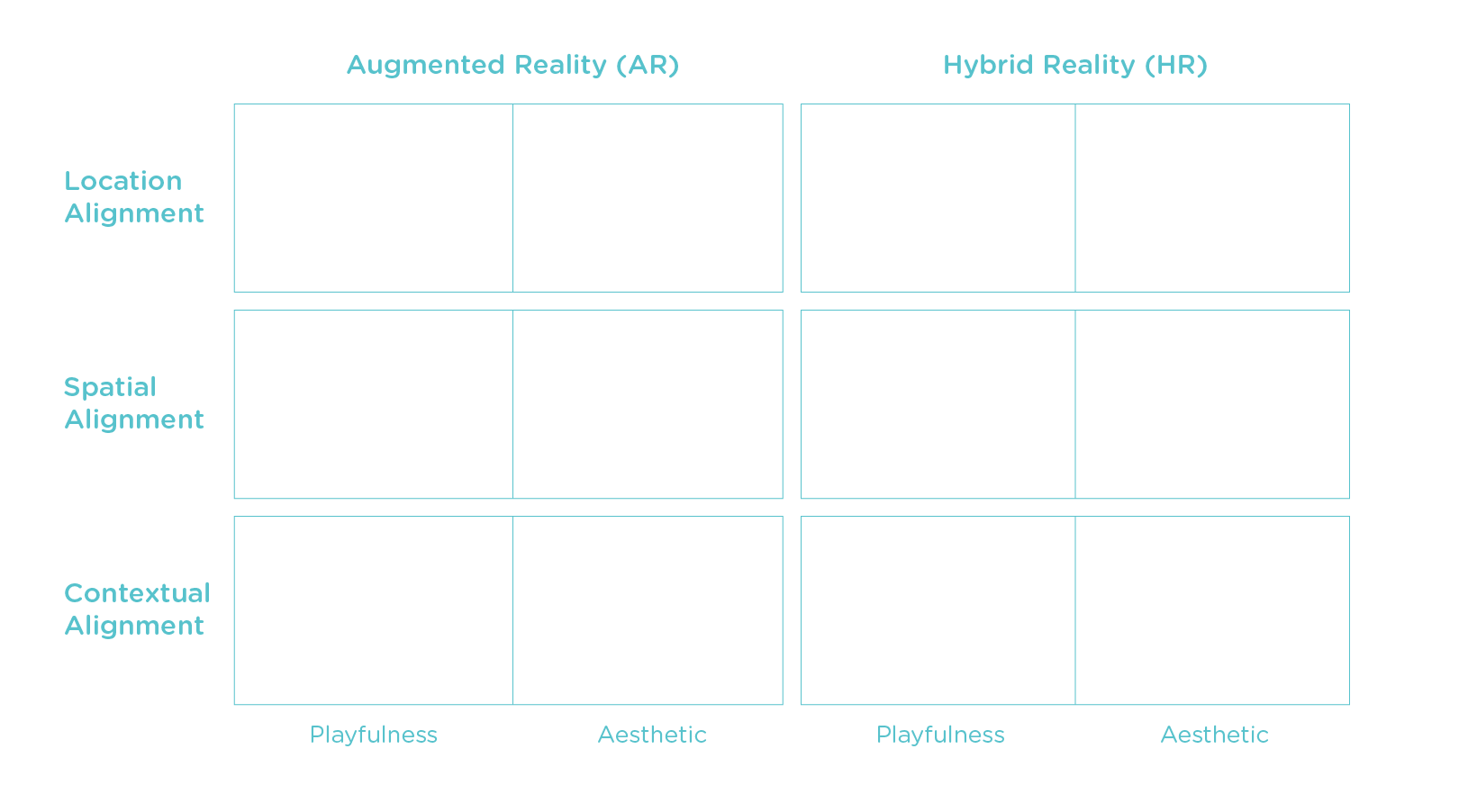

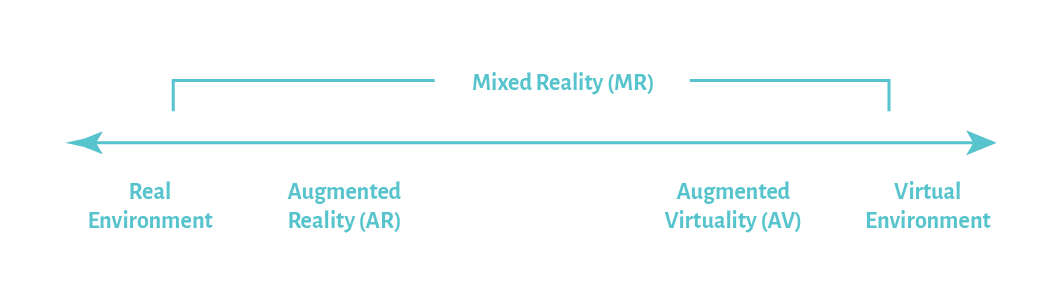

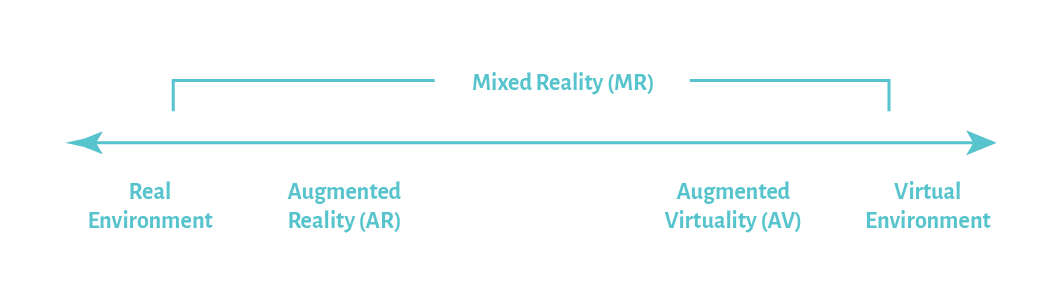

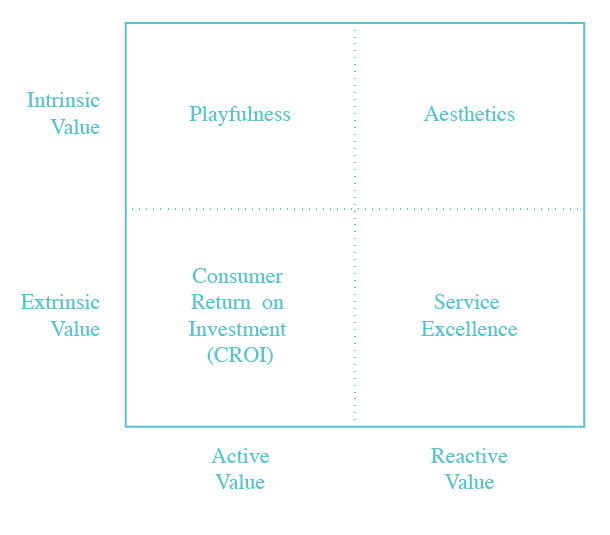

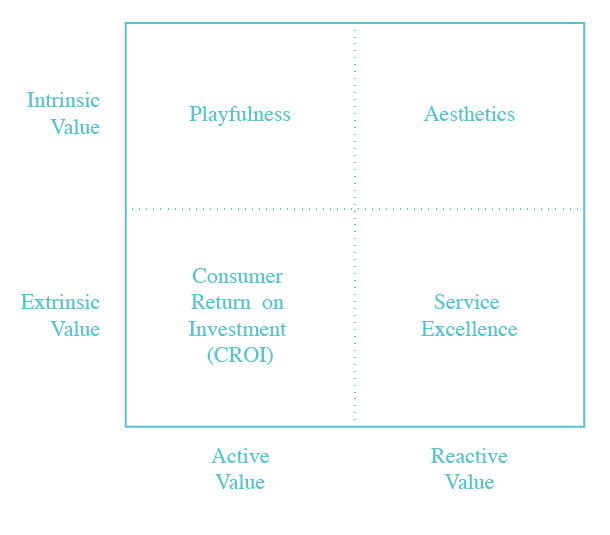

Combining the Mobile Media Alignment framework (Fig. 10)  , Virtuality Continuum (Fig. 11)

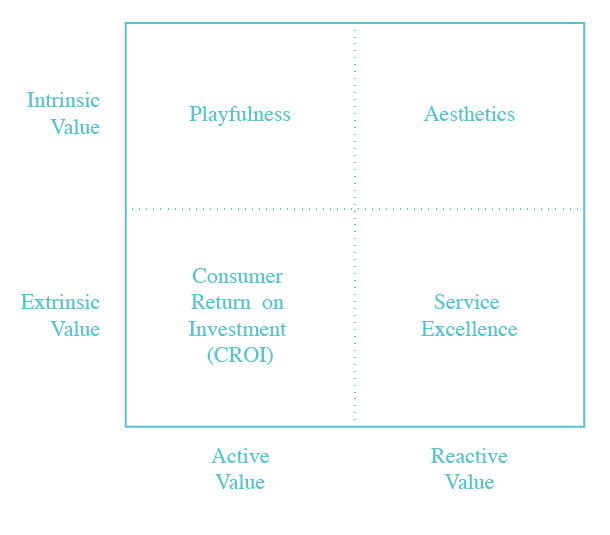

, Virtuality Continuum (Fig. 11)  , and the Experiential Value taxonomy (Fig. 12)

, and the Experiential Value taxonomy (Fig. 12)  , I developed a conceptual matrix (Table 1)

, I developed a conceptual matrix (Table 1)  to ground the investigation into existing frameworks. Features of the mobile application and methods of implementation within the museum fall into individual cells within the matrix (Table 2)

to ground the investigation into existing frameworks. Features of the mobile application and methods of implementation within the museum fall into individual cells within the matrix (Table 2)  .

.

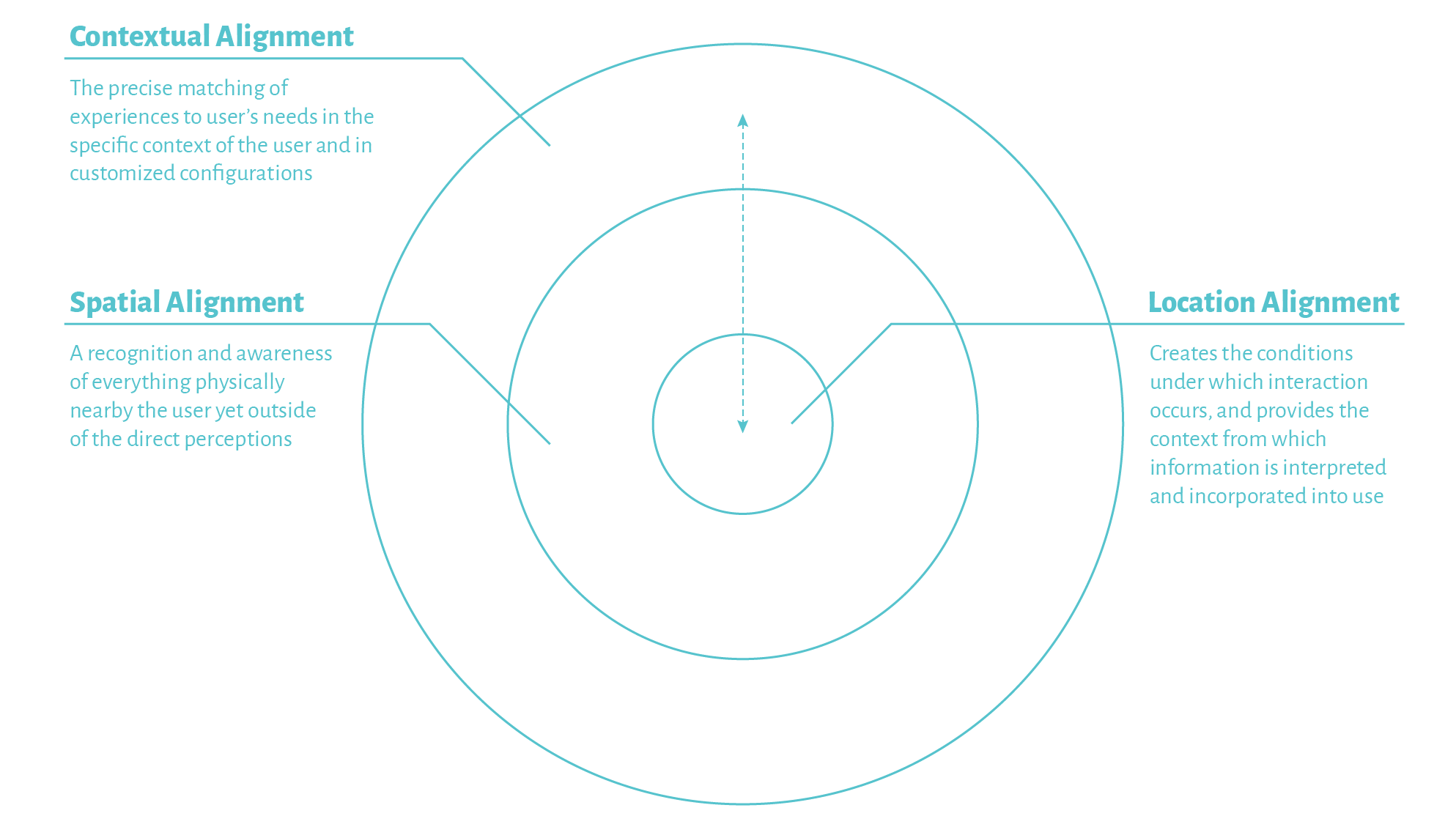

Table 1 - Combined Matrix

Brett Oppegaard, an Associate Professor in the School of Communications at the University of Hawaii, developed the Mobile Media Alignment framework to serve as a conceptual guide for designing human-centered augmented reality experiences. Oppegaard suggests that designers put the framework into a practical use and create experiences that effectively align digital information over physical environments based on a three-tier Mobile Media Alignment strategy that consists of location, spatial, and contextual alignments. According to Oppegaard, the three-tier guidance system, “is an idea that could lead people, especially designers and users, toward a new perspective on augmented reality and augmented places it can create.” Fig. 10  is a visualization of the Mobile Media Alignment framework.

is a visualization of the Mobile Media Alignment framework.

Fig. 10 - Mobile Media Alignment Framework

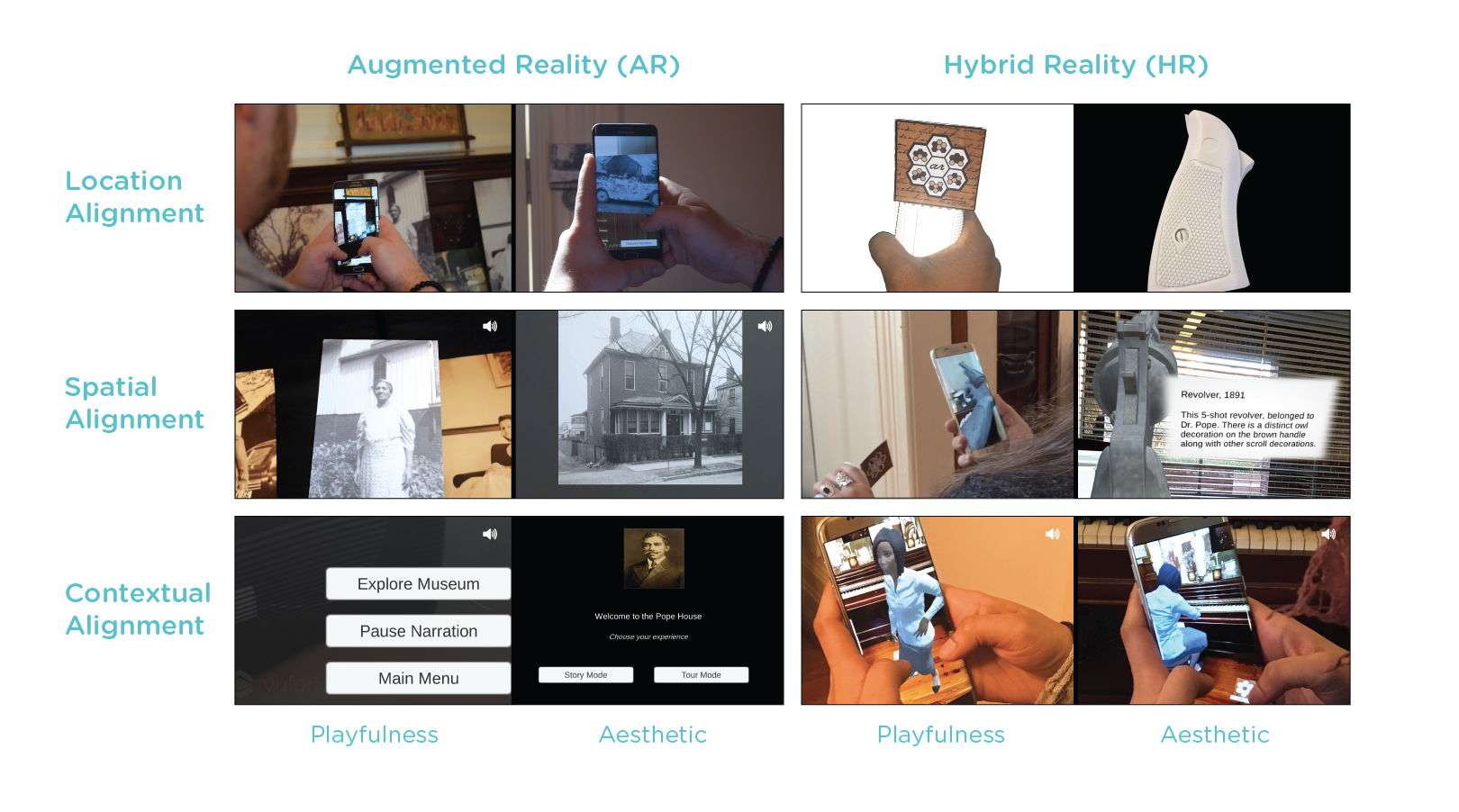

The Virtuality Continuum is a framework developed by Paul Milgram and Fumio Kishino to categorize different mixed reality displays. The authors identified six classes of mixed reality display environments used as metrics for distinguishing the various subsets of mixed reality experiences. Initial studies explored various forms of experiences along the virtuality continuum. Later explorations considered only the use of augmented reality and hybrid reality displays (Fig. 11)  . I define augmented reality as cases in which two information types, visual and verbal cues, augment a real environment using see-through hand-held displays. Although hybrid reality (HR) is not explicitly located on the virtuality continuum, I refer to HR as cases in which direct interaction between virtual and physical artifacts takes place. Therefore, I place HR in the gray area between augmented reality and augmented virtuality on the Virtuality Continuum.

. I define augmented reality as cases in which two information types, visual and verbal cues, augment a real environment using see-through hand-held displays. Although hybrid reality (HR) is not explicitly located on the virtuality continuum, I refer to HR as cases in which direct interaction between virtual and physical artifacts takes place. Therefore, I place HR in the gray area between augmented reality and augmented virtuality on the Virtuality Continuum.

Fig. 11 - Virtuality Continuum

The experiential value taxonomy is a system for categorizing key attributes that influence consumer behavior. The investigation excludes the extrinsic value dimension from the taxonomy and considers only intrinsic, active, and reactive values (Fig. 12)  . The exclusion of extrinsic values is due to the research’s primary focus on the types of mixed reality experiences used to enhance the museum visitation experience. The investigation places less consideration on the actual devices (mobile phones, head-mounted displays, etc.) used to view mixed reality experiences. Therefore, playfulness and aesthetics response are the only two attributes adapted from Mathwick and colleagues’ experiential value taxonomy and Holbrook’s Consumer value framework. I refer to playfulness and aesthetic values as self-oriented experiences. The differentiating factor between playfulness and aesthetics is that playfulness involves an active engagement within an activity; Whereas aesthetics value refers to an appreciation of the design or beauty of the experience.

. The exclusion of extrinsic values is due to the research’s primary focus on the types of mixed reality experiences used to enhance the museum visitation experience. The investigation places less consideration on the actual devices (mobile phones, head-mounted displays, etc.) used to view mixed reality experiences. Therefore, playfulness and aesthetics response are the only two attributes adapted from Mathwick and colleagues’ experiential value taxonomy and Holbrook’s Consumer value framework. I refer to playfulness and aesthetic values as self-oriented experiences. The differentiating factor between playfulness and aesthetics is that playfulness involves an active engagement within an activity; Whereas aesthetics value refers to an appreciation of the design or beauty of the experience.

Fig. 12 - Experiential Value Taxonomy

MATRIX OVERVIEW

I developed the prototype with the goal of granting visitors agency to decide the lens through which they experience the variety of historical narratives present in the home. Here’s an overview of how the conceptual matrix informed the design and development of the mobile application prototype.

Table 2 - Completed Matrix

Oppegaard refers to location as the conditions under which interaction occurs and the context from which we incorporate information into use. It is through location alignment that both spatial and contextual alignment becomes a possibility. For the augmented reality experience, I regarded location as the places within the museum where augmentation would take place. In the house museum environment, location alignment refers to the means through which the mobile application would initiate mixed reality experiences based on the visitor’s position within the home. During observational studies at the Pope House Museum, I observed that the piano in the former parlor of the museum was an important artifact and location where visitors frequently gathered during tours. The AR mobile application utilizes photos placed on the piano as image markers to trigger augmented experiences that present information about the family to visitors using visual and verbal cues.

I used a window in the formal parlor to explore spatial alignment features of the AR mobile application. During tours, Visitors gather at the window and look outside as docents describe what the exterior of the home looked like during the nineteenth century. To provide visitors with spatial information, I used an AR marker placed on the window frame to trigger visual cues. As visitors point their smartphone’s camera at the marker, a historic view of the exterior of the home renders over the window frame.

Oppegaard defines Contextual Alignment as the precise matching of experiences to the user’s needs in the specific context of the user and in customized configurations. Specifically, this exploration refers to contextual alignment as an act of providing agency to visitors to decide their visitation preferences. Data collected from the observation study informed the development of features within the AR mobile application that allows visitors to choose between two visitation modes. In Story Mode, a virtual docent guides visitors through the museum in a scripted sequential progression. Tour Mode allows visitors to freely explore the museum and receive information cues by interacting with artifacts based on their interests.

According to Steven Neale and colleagues, handling artifacts provides a spatial and physical understanding of the artifact [10]. Docents advised visitors to not touch exhibited artifacts during observed visitation tours at the Pope House. Therefore, when considering location alignment for the Addy 6 hybrid reality experience, I used 3D printed objects as triggers to render virtual models of museum artifacts that visitors could physically hold and interact with.

Artifacts in the display case at Pope House were taken from various locations within the home and exhibited in the dining area. Spatial Alignment in the HR exploration involves providing visitors with information about the origins of encased artifacts and how the family used them within the home.

For the HR contextual alignment exploration, I considered how the application could enable virtual avatars of family members to present historical narratives of the home to visitors. A feature incorporated within the prototype allows visitors to point their device’s camera at a marker to trigger a virtual avatar of a family member playing the piano. Visitors also have the agency to choose between virtual avatars of specific family members to interact with during the tour.

Both the augmented reality and hybrid reality experiences incorporate elements of playfulness and aesthetic values. Mathewick and colleagues refer to playfulness as an active engagement within an activity. Holbrook describes aesthetic value as an appreciation of some consumption experience. As both values are self-oriented, the researcher designed the prototype to give visitors agency to tour the home through a docent-guided (story mode) or self-guided (tour mode) approach. Through play, the interactive artifacts and dynamic information cues provide opportunities for visitors to actively engage with historical narratives present in the home.

USER TESTING

Testing the prototype at the Pope House (Fig. 13)  was an essential part of the research investigation. Data collected from the visitors and docents during the user test provided insights on the usability of trackers in different lighting conditions, and the user experience of the mixed reality system. Participants began the user test at the start of the tour and received instructions on how to use the application only upon equest. With the participants’ consent, the researcher captured photos and videos as they interacted with the mobile application for documentation and further analysis.

was an essential part of the research investigation. Data collected from the visitors and docents during the user test provided insights on the usability of trackers in different lighting conditions, and the user experience of the mixed reality system. Participants began the user test at the start of the tour and received instructions on how to use the application only upon equest. With the participants’ consent, the researcher captured photos and videos as they interacted with the mobile application for documentation and further analysis.

Fig. 13 - Participants user test the prototype

The museum managers and docents were excited about the potential of the prototype and how mixed reality can contribute to the preservation of the Pope House’s tangible and intangible cultural artifacts. The docents were able to use the application with little instructional guidance.

Feedback from docents included suggestions on placement of AR markers within the home and changing the names of the visitation modes (Story Mode and Tour Mode) to be more concise descriptors of the two experiences. Most visitors stated that they preferred Tour Mode over Story Mode, as the former provided more information about the Pope family and was less scripted than the latter. Visitors acknowledged that holding the 3D printed handle and using it to interact with virtual artifacts made the visitation tour much more engaging.

During the user test, the researcher observed that photos used as markers were much easier to track and provided little interruption. In contrast, the designed AR markers (VuMarks) were more difficult to track due to their small size and low lighting within the museum. Markers placed on the floor provided more interruptions than those within arm’s reach of participants.

FINAL PROTOTYPE

Based on the feedback and analysis of the user-test, I revised the prototype to incorporate the suggestions made by the docents and visitors. The following scenario video (Fig. 14)  shows Natalie, as she visits the Pope House Museum after the implementation of the mixed reality system.

shows Natalie, as she visits the Pope House Museum after the implementation of the mixed reality system.

Fig. 14 - Scenario video showcasing the final prototype

In the video, we saw Natalie tour the home using the Explore Museum visitation mode. The second visitation experience, Visit Family, gives visitors the option to join a member of the Pope family to on a story-based immersive tour of the home. Each story is told from the perspective of the family member the visitor chooses. Stories are based on national and local historical events of the 20th century that have a relevant connection to the Pope Family.

This investigation explored how house museums can implement mixed reality systems to increase visitors’ satisfaction. The goal of this research was to emphasize the cultural significance of house museums and contribute to its preservation through mixed reality experiences that complement exhibited artifacts within the home. It was important that the implementation of the system did not seem out of context, but instead provided an additional lens through which visitors can experience the historical narratives present in the home.

Situating the investigation in a real-world context at the Pope House Museum was an essential part of the design process. Gathering factual historical data about the Pope family to develop the prototype allowed the researcher to test the mobile application in-situ and collect feedback from the museum visitors to improve the system’s usability. Working with the museum staff and visitors to realize the objectives of the project further emphasizes the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of the investigation. Designers, curators, and educators alike must continue to work together to find innovative ways to contribute to the preservation of historic house museums.

Future investigations should consider how mixed reality experiences developed to complement house museum visitation can facilitate interaction between museum visitors. Designers must regard the house museum as a collective memory shaped by the family that once lived in the home, and community members of today that continue to walk in the footsteps of the homeowner’s historic legacy.

G. Pinna, “Introduction to historic house museums,” Museum International, vol. LIII, no. 2, pp. 4-9, April 2001.

L. Young, Historic House Museums in the United States and the United Kingdom: A History, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016, ch. 1.

M. Risnicoff de Gorgas, “Reality as illusion, the historic houses that become museums,” Museum International, vol. LIII, no. 2, pp. 10-15, April 2001.

Z. He, L. Wu, X. Li, “When art meets tech: The role of augmented reality in enhancing museum experiences and purchase intentions,” Tourism Management, vol. 68, pp. 127-139, October 2018.

L. A. P. Barker, “Repurposing Museum Interpretation in American Historic House Museums,” Ph.D. dissertation, School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester, Leicester, England, 2017.

K. L. Zogry, “The house that Dr. Pope built: Race, politics, memory, and the early struggle for civil rights in North Carolina,” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2008.

B. Martin, and B. M. Hanington, Universal Methods of Design: 100 ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions, Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers, 2012.

E. Craig. (January 21, 2019). “I Am A Man” VR Experience puts you inside the Civil Rights Movement. Retrieved February 14, 2019, from https://www.digitalbodies.net/vr-experience/i-am-a-man-vr-experienc e-puts-you-inside-the-civil-rights-movement/.

J. Hurdle. (September 29, 2017). Arming China’s terracotta warriors – with your phone. Retrieved March 22, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/29/science/china-terracotta-warrior s-augmented-reality.html.

P. West. (June 22, 2018). Tour the Historic Anne Frank House in VR. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from https://vrscout.com/news/tour-the-anne-frank-house-in-vr/.

(November 12, 2018). New Augmented Reality App Brings Oxford to Life Like Never Before. Retrieved March 22, 2019, from https://www.experienceoxfordshire.org/new-augmented-reality-app-br ings-oxford-to-life-like-never-before/.

P. Milgram, and F. Kishino, “A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays,” IEICE Transactions on Information Systems, vol. E77-D, no. 12, pp. 1-15, Spring 2001.

C. Mathwick, N. K. Malhotra, and E. Rigdon, “Experiential Value: Conceptualization, measurement, and application in the catalog and internet shopping environment,” Journal of Retailing, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 39-56, 1994.

M. B. Holbrook, “Introduction to consumer value,” in Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research, M. B. Holbrook, Ed. New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge, 1999, pp. 1–28.

M. B. Holbrook, “Customer value and autoethnography: subjective personal introspection and the meanings of a photograph collection,” Journal of Business Research, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 45–61, January 2005.

B. Oppegaard, “Designing, Arranging, and Assessing Augmented Places through Mobile Media Alignment,” in Augmented Reality: Innovative Perspectives across Art, Industry, and Academia, S. Morey, and J. Tinnell, Eds. Anderson, South Carolina: Parlor Press, pp. 26-44.

S. Neale, W. Chinthammit, C. Lueg, and P. Nixon, “RelicPad: A Hands-On, Mobile Approach to Collaborative Exploration of Virtual Museum Artifacts,” Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2013. INTERACT 2013. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Eds. P. Kotze, G. Marsden, G. Lindgaard, J. Wesson, M. Winckler, pp. 86-103, vol. 8117, 2013.